ARE PROCESSED FOODS BAD FOR YOU?

Last week I shared some stories where I showed that right now I’m using 0% Greek yogurt instead of cream in my kaiserschmarren. This change allows me to save 77 kcal every day. I decided to lower my calorie intake because, due to my knee, I can’t move as much as before and my energy expenditure has gone down.

After those stories, I received A LOT of messages:

- Low-fat yogurt isn’t good, it’s a processed product (because the fat is removed).

- The fats in yogurt are essential to keep blood sugar stable.

- You’ve always said fats are fundamental for our body.

- This sudden change of yours leaves me puzzled.

From these messages came an interesting deep dive, which I’ve decided to publish here as well.

Let’s look at the comments:

You’ve always said fats are fundamental for our body.

This sudden change of yours leaves me puzzled.

In kaiserschmarren with 0% Greek yogurt there are 18 g of fat, compared to 29 g when made with cream. So yes, it still contains fat just 38% less. Less fat means fewer calories: 537 instead of 614, which is 77 kcal less. I’m still eating a dish that contains fat, just with less of it. This isn’t a radical change, just a temporary decision to reduce my calorie intake for a specific goal.

The fats in yogurt are essential to keep blood sugar stable.

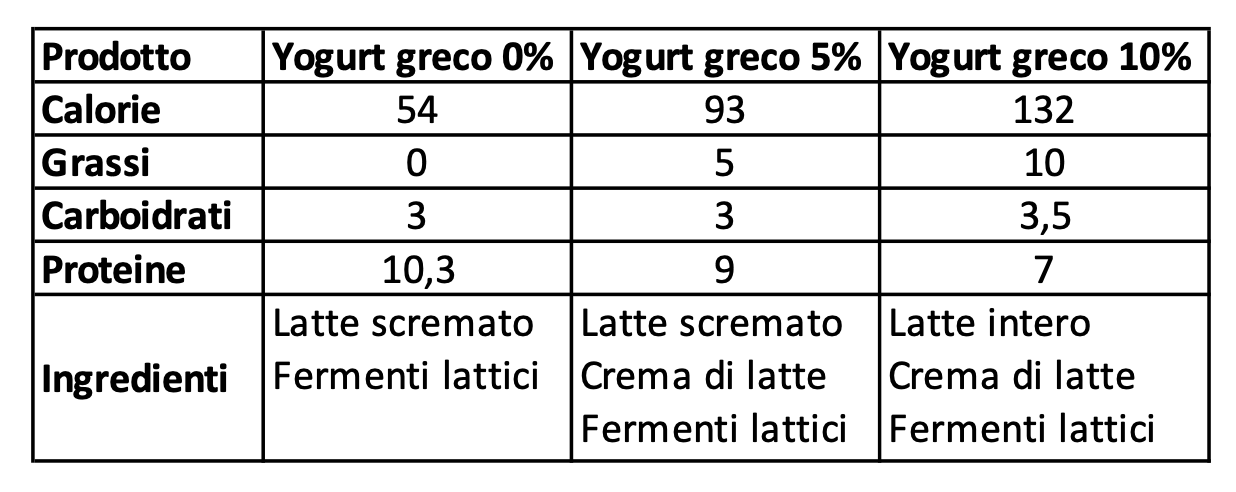

As you can see from this chart, 100 g of 0% Greek yogurt contain only 3 g of carbs. So even if I ate it alone, its effect on blood sugar would be minimal. And in this case, it was just one ingredient in the kaiserschmarren, which already contained another 18 g of fat. Context is everything.

Low-fat yogurt isn’t good, it’s a processed product because the fat is removed.

Milk is made up of water, proteins, fat, lactose, vitamins, and minerals. Fat globules float in suspension because fat and water don’t mix. If you shake water and oil you create anemulsion which will later separate. If you shake water and sugar, the sugar dissolves it’s a solution.

Years ago, I spent a few days in the Alps. Fresh milk was stored in aluminum cans placed in cold running water. The next morning, cream had risen to the top—a natural separation of fat. The richest, creamiest cream I’ve ever tasted! This process is called spontaneous creaming.

The food industry uses a different method: centrifugation. A simple process that exploits the different density of fat and the watery part of milk. We use centrifugation at home too—to spin salad dry, or in washing machines.

Both spontaneous creaming and centrifugation give us two products: cream and skimmed milk. So yes, both are processed foods. But does that mean they’re harmful?

In this article you can find a technical description of the two processes.

WHAT DOES “PROCESSED FOOD” MEAN?

First, let’s define it: a processed food is any food that has been modified, industrially or domestically, from its natural state. Cooking is a process. So is chopping, peeling, freezing, fermenting, sprouting, blending, etc.

So, calling a food “processed” doesn’t automatically make it harmful it just means it’s been through a process.

Many processes we use in the kitchen have been around since the dawn of humanity. Industrial processes are much more recent, and their impact has often been underestimated. Since the 1980s, industrial foods have multiplied, and at the same time, our health has worsened. But is the problem the process itself—or the ingredients used? Let’s find out.

THE NOVA CLASSIFICATION

In 2010, Brazilian researcher Carlos Monteiro published the first study attempting to classify processed foods: “A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing” (1). From this study came the NOVA classification. (NOVA isn’t an acronym it simply means “new” in Portuguese.)

Monteiro later published two more studies (2,3) with over 2,000 citations each (a huge number).

Here are the four NOVA groups

Group 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

Minimally processed foods are natural foods altered by processes such as the removal of inedible or unwanted parts, drying, crushing, grinding, roasting, boiling, pasteurization, refrigeration, freezing, packaging, vacuum-sealing, or non-alcoholic fermentation. None of these processes add substances like salt, sugar, oils, or fats to the original food. The main purpose is to extend the shelf life of grains, legumes, vegetables, fruit, nuts, milk, meat, and other foods, making them easier to store, prepare, or use in different ways.

Examples: fresh or dried fruit, vegetables, legumes, grains, tubers and roots, flours and polenta, eggs, milk (including skimmed), yogurt (including low-fat), whole cuts of meat and fish, fresh or dried mushrooms, seaweed, herbs, spices, coffee beans, nuts and seeds. Low-fat yogurt belongs to Group 1.

GROUP 2: Processed culinary ingredients

These are substances obtained directly from Group 1 foods or from nature through processes such as pressing, refining, grinding, or spray-drying. They are used in home or restaurant kitchens to prepare, season, and cook Group 1 foods.

Examples: salt extracted or derived from seawater; sugar from cane or beets; maple syrup and honey; vegetable oils pressed from olives or seeds; butter and lard; starches extracted from corn and other plants.

GROUP 3: Processed foods

These are relatively simple products made by adding sugar, oil, salt, or other Group 2 substances to Group 1 foods. Most processed foods contain two or three ingredients. Processes include preservation methods, cooking, or non-alcoholic fermentation. The main goal is to increase shelf life or improve taste and texture. They may contain additives.

Examples: canned or bottled vegetables, fruits, and legumes; salted or sweetened nuts and seeds; cured, smoked, or salted meats; canned fish; fruit in syrup; cheeses; fresh unpackaged bread.

GROUP 4: Ultra-processed foods

The fourth NOVA group includes ultra-processed foods, which are industrial formulations made from multiple ingredients, some derived from extensive processing and combined with other processes (hence the term “ultra-processed”). Their ingredients often include those also found in processed foods (sugar, oils, fats, salt), but also others not normally used in home cooking. Some are directly extracted from foods (casein, lactose, whey, gluten), while others come from further industrial processing, such as hydrogenated or interesterified oils, hydrolyzed proteins, soy protein isolate, maltodextrin, inverted sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, etc.

Additives in ultra-processed foods include some that are also used in processed foods, such as preservatives, antioxidants, and stabilizers, as well as others found only in ultra-processed products, used to imitate or enhance the sensory qualities of food or to mask undesirable aspects of the final product. These additives include colorings, stabilizers, flavorings, flavor enhancers, sweeteners, and processing aids such as leavening agents, firming agents, bulking and anti-bulking agents, anti-foaming agents, anti-caking agents, glazing agents, emulsifiers, sequestrants, and humectants.

A multitude of processing sequences are then used to combine all these ingredients into the final product hence “ultra-processed.” Many of these processes have no equivalent in home cooking, such as hydrogenation, hydrolysis, extrusion, molding, and more.

The overall purpose of ultra-processing is to create branded food products that are convenient (long shelf life, ready to consume), appealing (hyper-palatable), and highly profitable (made with low-cost ingredients), designed to replace all other food groups. Ultra-processed foods are usually attractively packaged and heavily marketed.

Examples: soft drinks, packaged snacks, confectionery, industrial breads and flatbreads, margarines and spreads, cookies, pastries, cakes and cake mixes, breakfast “cereals,” cereal and “energy” bars, “energy” drinks, flavored milk and yogurt drinks, fruit drinks, cocoa drinks, meat and chicken extracts, instant sauces, infant formulas, follow-on milks and other baby products, “health” and “diet” products, many ready-to-heat meals, reconstituted meat products, as well as instant soups, noodles, and desserts.

REFLECTIONS

The NOVA classification is a great starting point, but it’s not definitive. Knowledge keeps evolving (fortunately!), and many healthy products (collagen, whey, essential amino acids, omega-3s, …) are obtained through complex processes that fall under “ultra-processed.”

This shows that a complex or high-tech process is not harmful per se it depends on how it changes the raw material. For example, we now know that hydrogenated fats are very harmful, so hydrogenation is clearly negative. On the other hand, enzymatic hydrolysis breaks proteins into smaller amino acid fragments exactly what our digestive system does. Hydrolyzed proteins are more easily digested, so why should that be considered harmful?

Human beings tend to think in black-and-white, especially about something still relatively new. Industrial processing has been around for just over 50 years, so it’s somewhat natural that the current mindset is: “everything ultra-processed is bad.” But it’s not that simple. There are many shades of grey. For example, I’d rather choose an ultra-processed product with no additives (say, a protein blend made with whey, collagen, coconut milk, and cocoa) than a minimally processed product containing additives (like dried figs with sulfur dioxide). Personally, I try to avoid additives of any kind, but I value processing—even complex technological ones as long as it doesn’t make the food harmful.

I’m not the only one who thinks this way. Carlos Monteiro, the researcher who developed the NOVA classification, also wrote (3): “Virtually all food is processed in some way and to some extent. Therefore, the word ‘processed’ is very general and not very useful. It is a mistake to judge foods simply because they are ‘processed.’ Even attempts to distinguish different types of processes using vague terms such as ‘highly’ or ‘heavily’ processed, or ‘fast,’ ‘convenience,’ ‘snack,’ or ‘junk’ foods are equally unhelpful. Judgments about food processing itself carry little or no meaning. Food scientists and technologists, as well as producers, rightly emphasize the benefits of ancient or relatively recent processes, such as drying, non-alcoholic fermentation, refrigeration and freezing, pasteurization, and vacuum packaging. On the other hand, evidence of the harms caused by partial hydrogenation is now conclusive, as is evidence about the dangers of added sugars (especially in soft drinks).”

Let’s remember: in the 1980s we were told hydrogenated fats were healthier than saturated fats, and people were encouraged to choose margarine over butter. Luckily, the truth has since come to light.

Not all advanced technological processes should be demonized. It depends on how they modify the food.

As for products: those with endless ingredient lists filled with strange names, additives, flavors, etc. should definitely be AVOIDED. No doubt about that. But I don’t agree that simply because a food has undergone a highly technological process it must be harmful. Yes, it’s ultra-processed but that doesn’t automatically mean it’s bad. Again, it depends on how the process modifies the food.

Technology is a wonderful thing it should be used wisely, to our advantage. Today, much of the food industry uses it to create poor-quality products. But it won’t always be that way: once we stop buying such products, the industry will adapt and start producing clean ones. We are already beginning to see this shift.

I’ll close with a phrase I haven’t said in a while: every euro we spend is a statement about the future we want..

I hope this deep dive has helped raise awareness and with it, live better.

Knowledge sets one free.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21180977/

2) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10260459/

3) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10261019/

Leave A Comment